Notes on Stanford Linear Accelerator Center

2023-05-27

The latest of my "sixth grade class trip" adventures found me (and some co-workers) at SLAC - the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center.

Side note - my notes on previous "sixth grade class trips" include Nike Missile Site SF 88L and an REI Map and Compass Navigation course.

Maybe, like me, you've seen the SLAC sign countless times whilst driving down the SF peninsula past Menlo Park and wondered what sort of particle physics wonders were being conducted hundreds of feet beneath you and Interstate 280.

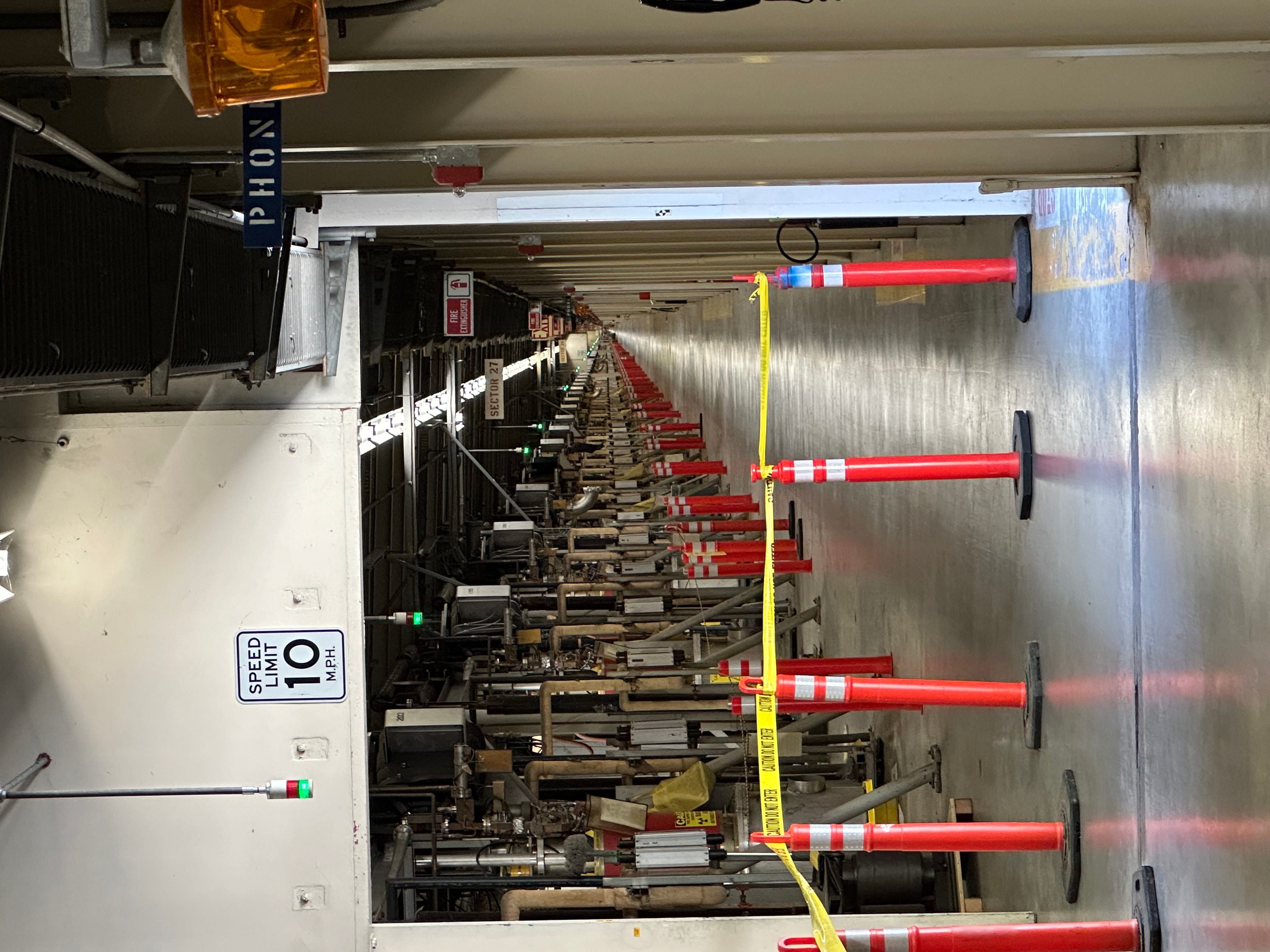

Well, now I know. And I have the obligatory two-mile long hallway selfie to prove it:

If you think you can see the end of this hallway, you're a liar! The human eye can't do it. Our guide told us so, and he was a scientist, okay? Okay!

For the so-tempted, SLAC offers a free tour, once per month, and I'm pretty sure it sells out faster than Phish tickets or Yosemite camping sites (bookmark this page if you want in!).

I've been daydreaming about visiting SLAC ever since I wrote a scene in my manuscript about someone accidentally discovering a particle accelerator beneath their parent's office -- and then subsequently realizing that I have no idea what a particle accelerator actually looks like.

Also, particle accelerators are just cool. You may be aware that the World Wide Web was created in one in 1989 - not directly influenced by hyper-charged electrons, of course, but also not-not-directly influenced either. Plus, this one -- SLAC -- also played host to some meetings of the Homebrew Computer Club during the 1970s.

I was therefore, understandably, quite excited when I successfully conjured tickets for the April tour, and then entered a building on Sand Hill Road for the first time.

SLAC tour walkthrough

The SLAC tour begins, excitingly, in a conference room where you watch a pre-recorded video, which despite a valient effort, is nowhere near as good as its Jurassic Park "frog DNA" counterpart. The SLAC video covers the Cold War era SLAC origin tale in the early 1960s, the fascinating Nobel-prize-inducing discoveries discovered here (including the charm quark and the tau lepton particle), the unplanned-obsolence of the primary linear accelerator, and its recent renewal for other cool x-ray stuff.

Approximately twelve minutes later, we hop in a bus and head on over to the linear accelerator, which from the surface, looks like a bunch of shipping-container style buildings in a row. A very long row. Here's Google Maps proof:

Inside this record-setting building (once the longest building the world), you'll first see a sample section of the accelerator itself (the rest of which is buried many feet below you).

The bigger silver pipe is called the Light Pipe and it helps align the smaller copper pipe above it where the particles travel. Because the accelerator is two miles long, they had to factor in the curvature of the Earth its contruction and its ongoing alignment. Though the advent of the laser pointer pen (you know, the thing your cool, but also kinda mean, middle school classmate secretly pointed at the guest speaker during an assembly about drugs or something) rendered the light pipe obsolete, the light pipe served its purpose effectively, helping align what was once the world's "most straight object."

After checking out this sample section of the accelerator, we're allowed to enter the "Klystron gallery".

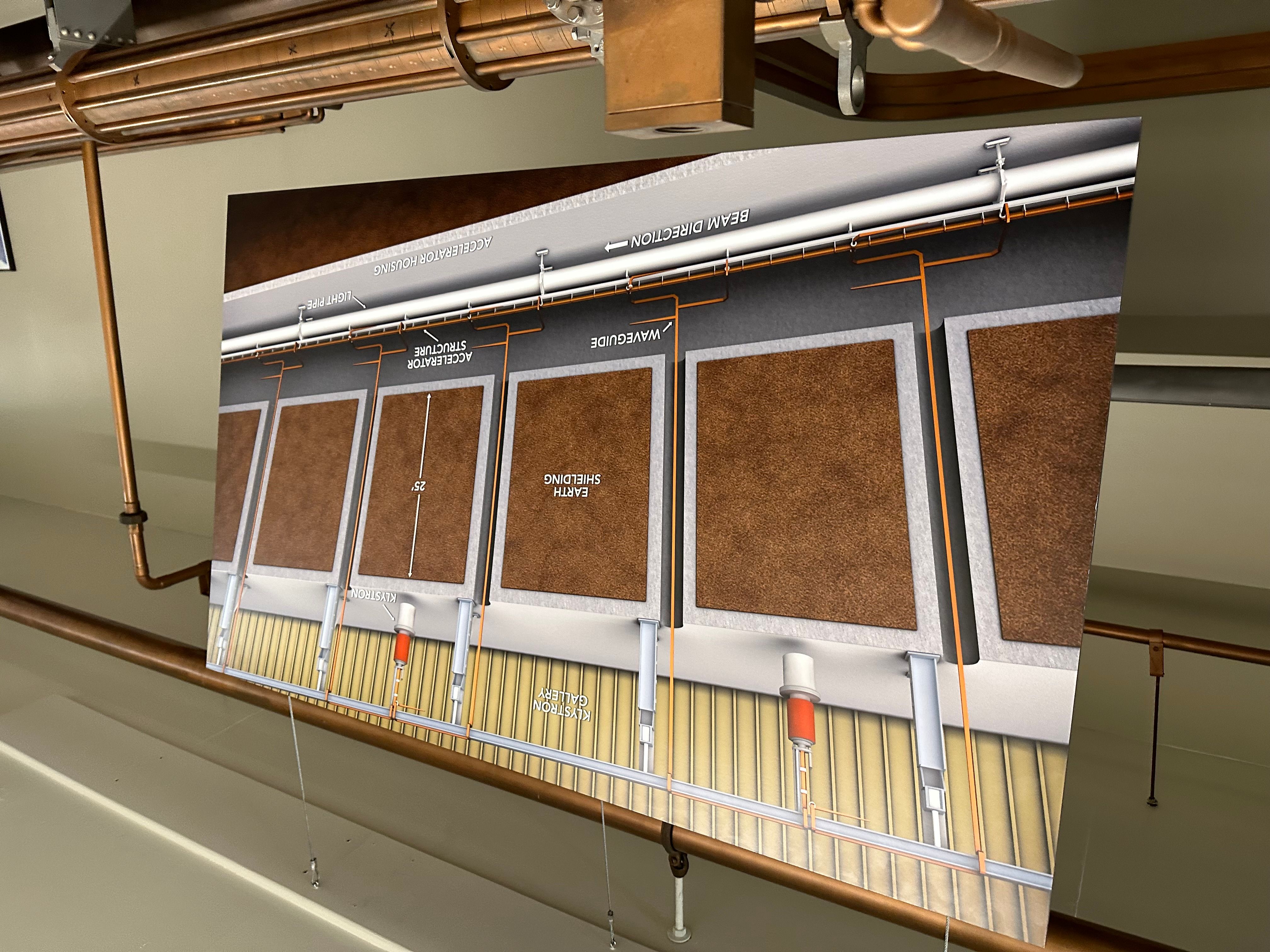

A Klystron is this big microwave thing that helps speed up the particles traveling along the accelerator. This is the best visual of what's going on where with these here klystrons.

The "gallery", where we are, is the top section. Below us, beneath many feet of "Earth shielding" which appears to be dirt based on this diagram, is the accelerator. Every X feet (I forget how many), a kytstron will send microwave-like energy down to the accelerator, and help ... accelerate ... the particles flinging along the path (electrons and positrons). The inside of the copper accelerator pipe looks like this, where the microwaves from the Klystron enter these open sections.

The pipe with the particles is also water-cooled, cause it gets real hot.

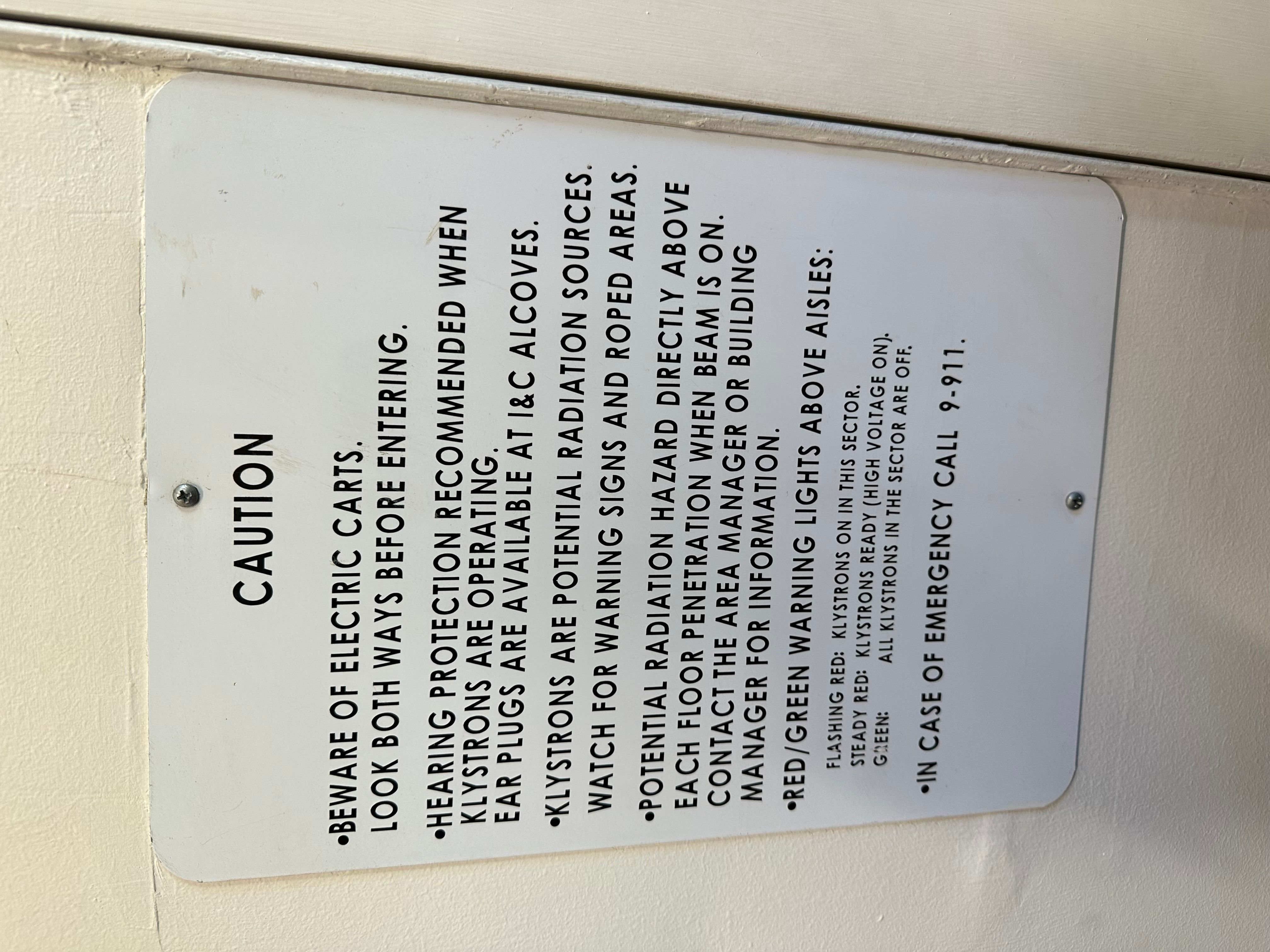

What else? Well, here's the caution sign right as you enter the Klystron gallery.

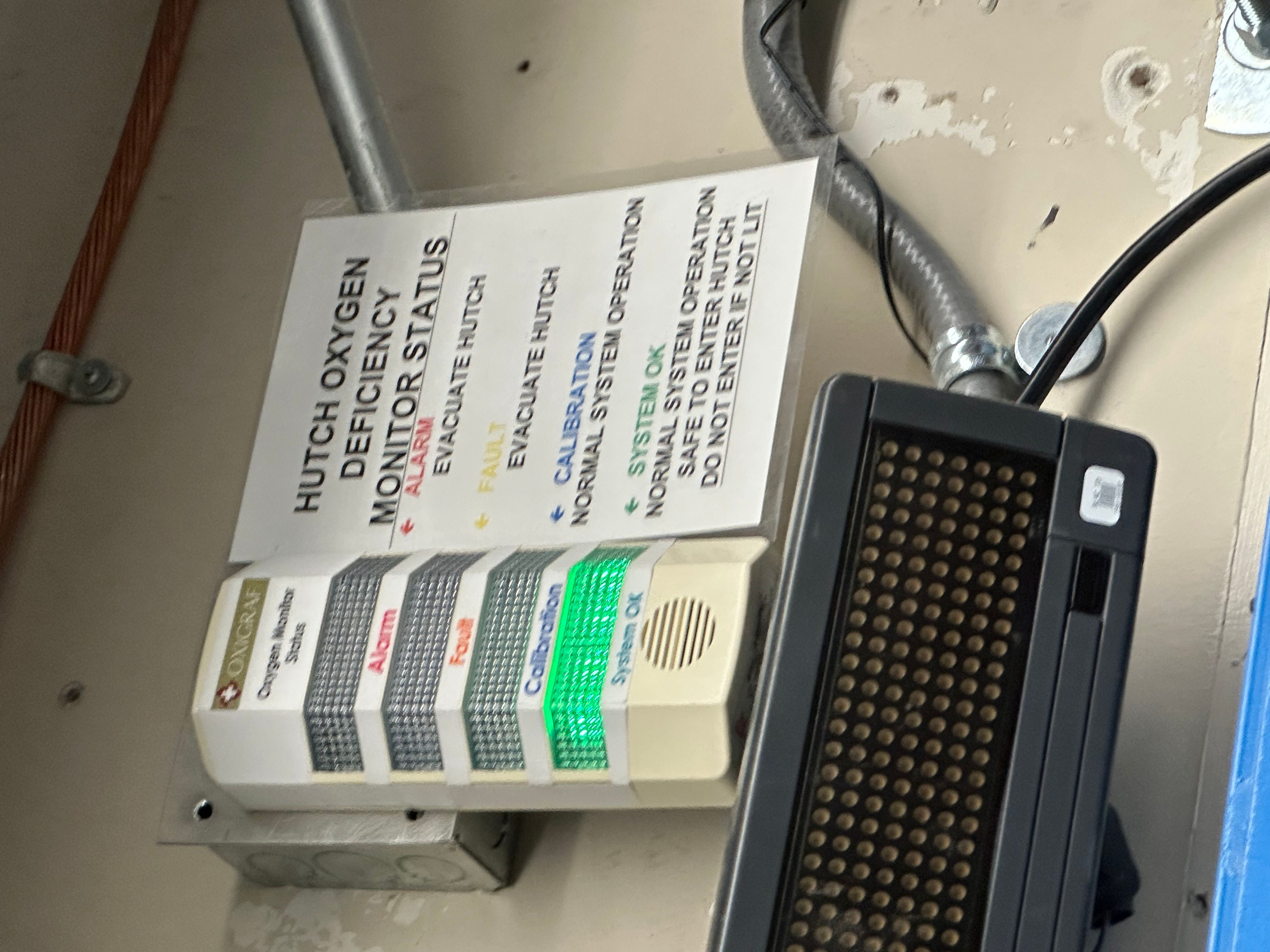

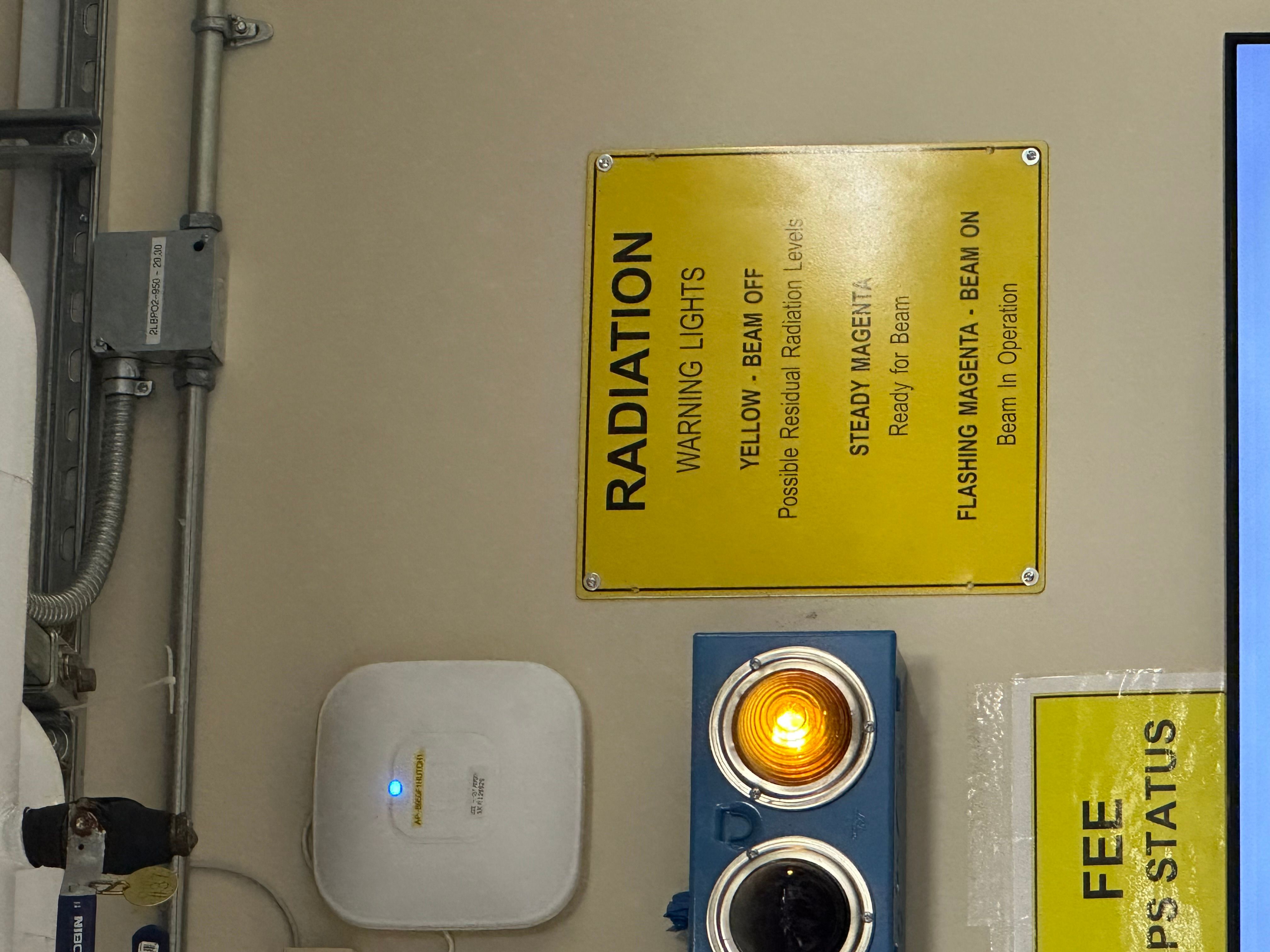

Is there radiation risk in here, you might ask? No more so than when you eat a banana, says our guide. However, we are still greeted with these warnings:

Not sure about that leaky window thing.

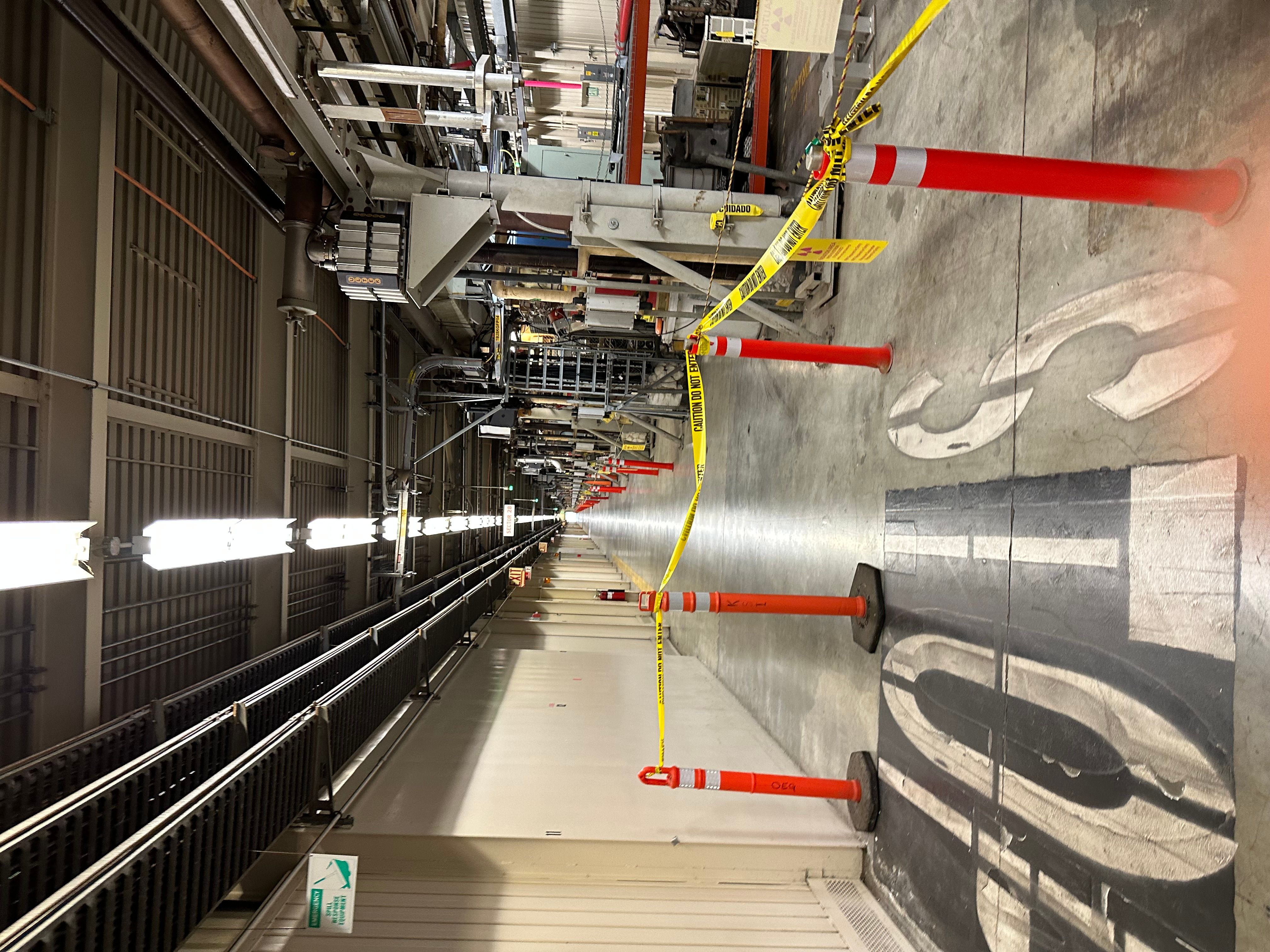

Here's the view of the gallery looking left:

And now looking right:

It really is trippy to look down this hallway. I asked our host if he'd ever run the full length. He chuckled (not sure if that was an affirmative), but did say that there used to be a 5k among the scientists, up and back along the accelerator. I'd love to have seen - or better run -- that race.

Science stuff

Eventually ,the SLAC linear accelerator lost steam, so to speak. You may be loosely aware that the top accelerators these days are all curved (e.g. CERN). Our host explained that electrons lose energy during a curve, so why did the curved accelerators win out? Mainly, money. Because each klystron in a linear accelerator can only be used "once" for a given particle -- the only way to speed things up even more would be to make the linear accelerator longer, and that's just impractical money-wise and land-wise. But a curved accelerator, even with energy-loss along the way, can reuse its klystrons (and the like) many, many, many times. Even SLAC ended up building some curved sections at the end of the accelerator.

All that to say that the linear accelerator is no longer used in the same way anymore. But scientists have built a bunch of other interesting things using components of the accelerator, like the Linac Coherent Light Source - a giant x-ray laser.

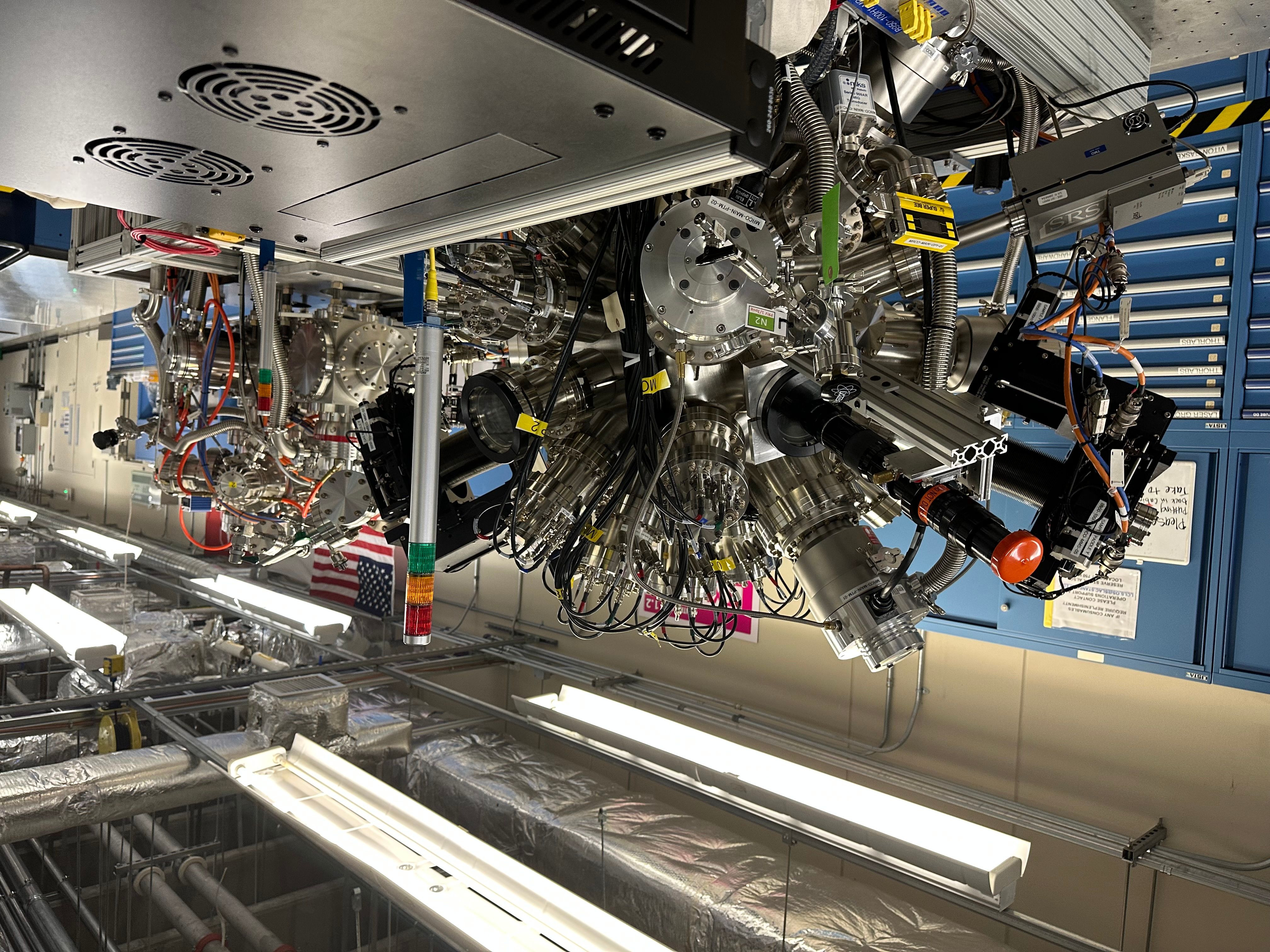

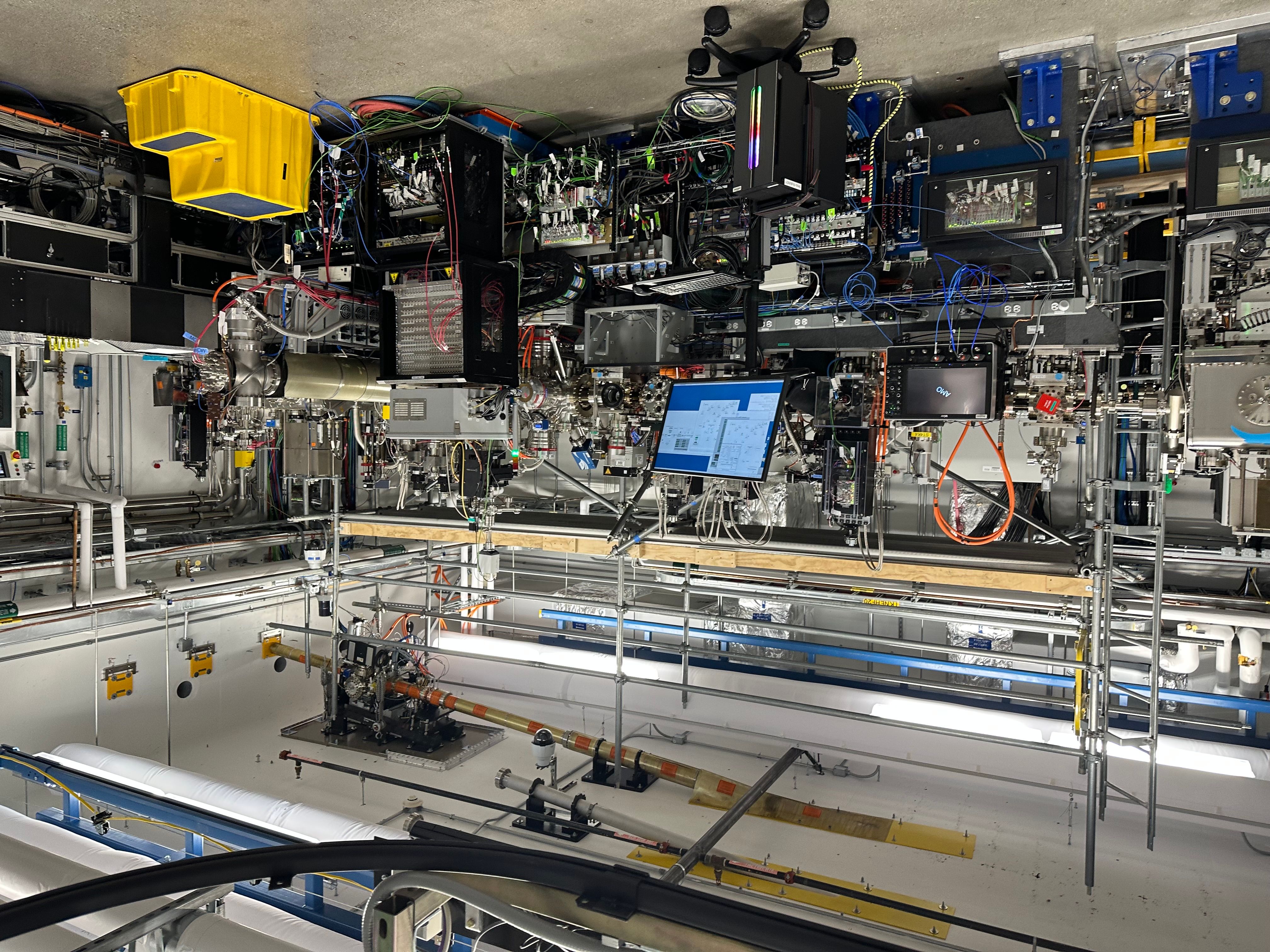

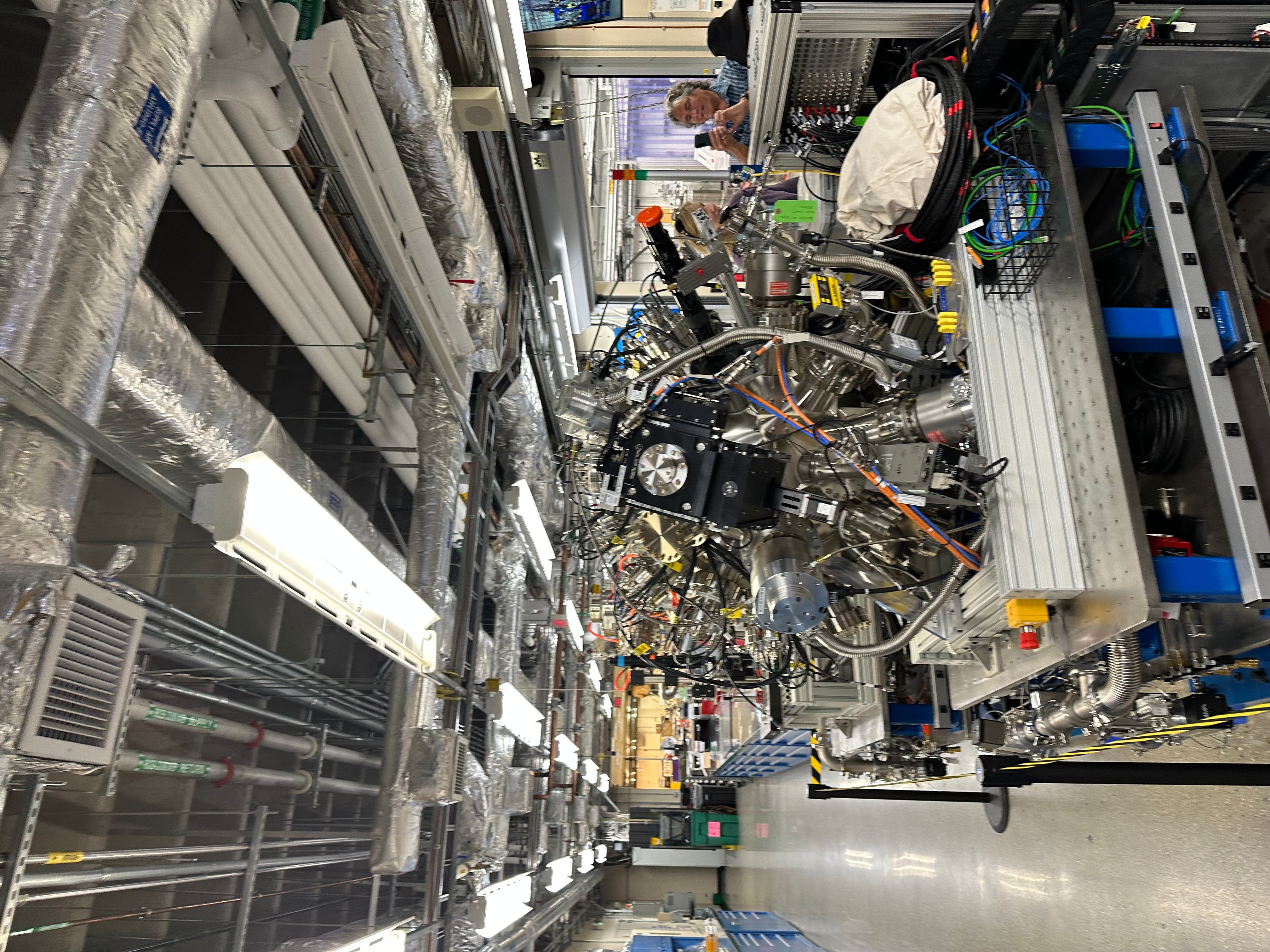

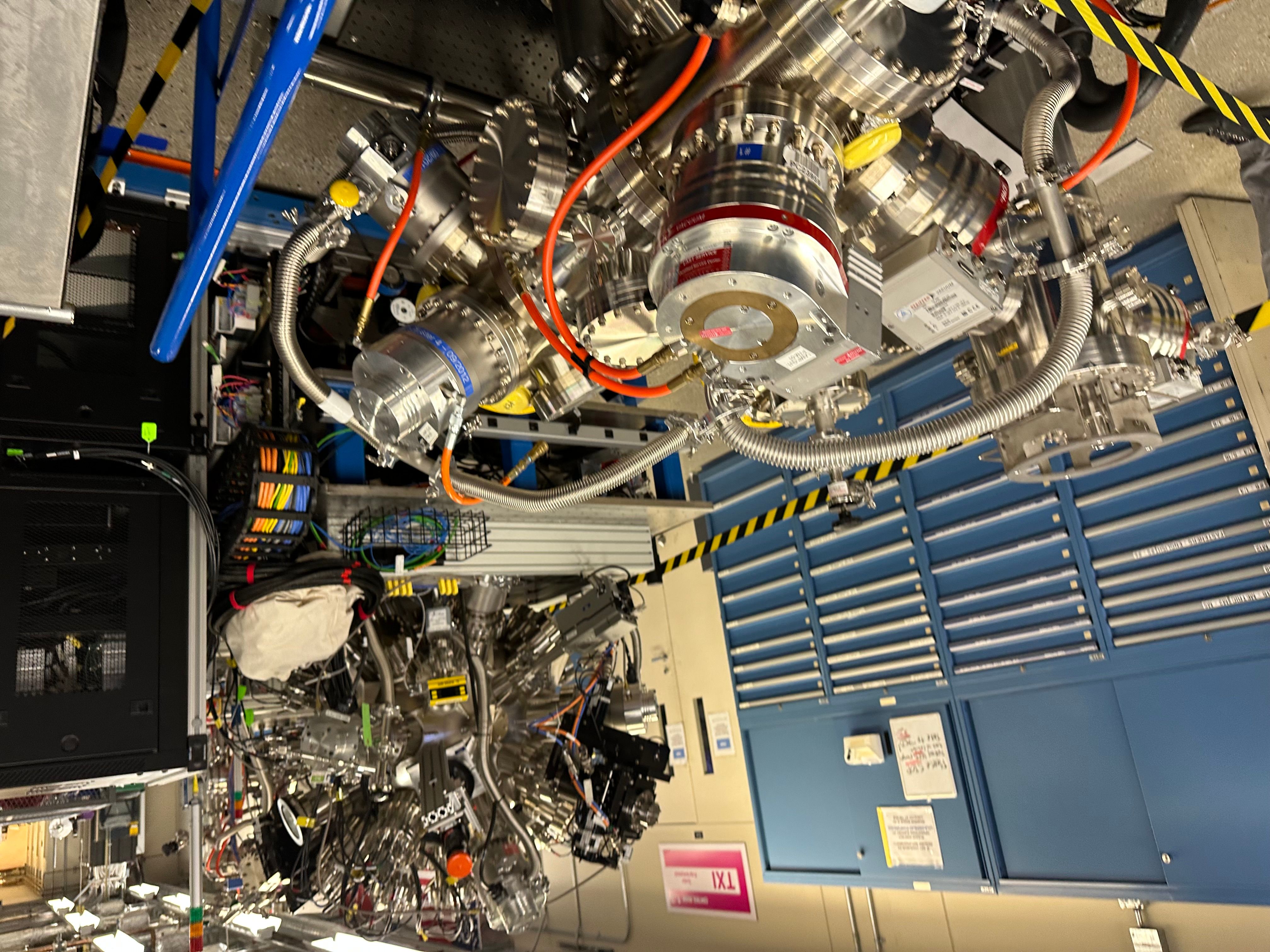

And for the next part of the tour, we got to see where these scientists are doing their science. And guess what? This part was even cooler than the endless hallway, because it felt active and alive and also like a space station.

Like, what the heck is this thing?

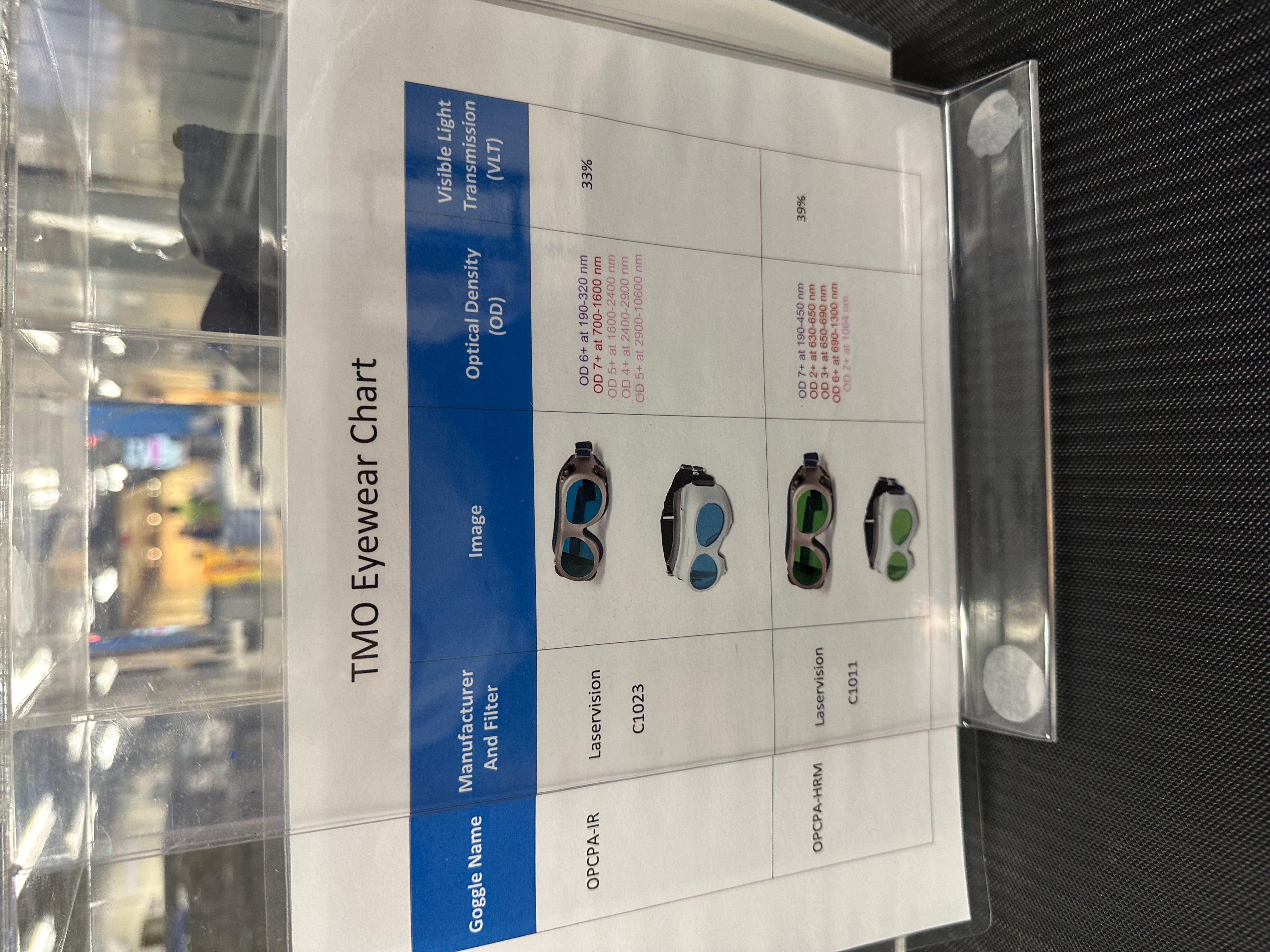

Better wear the correct goggles, or else!

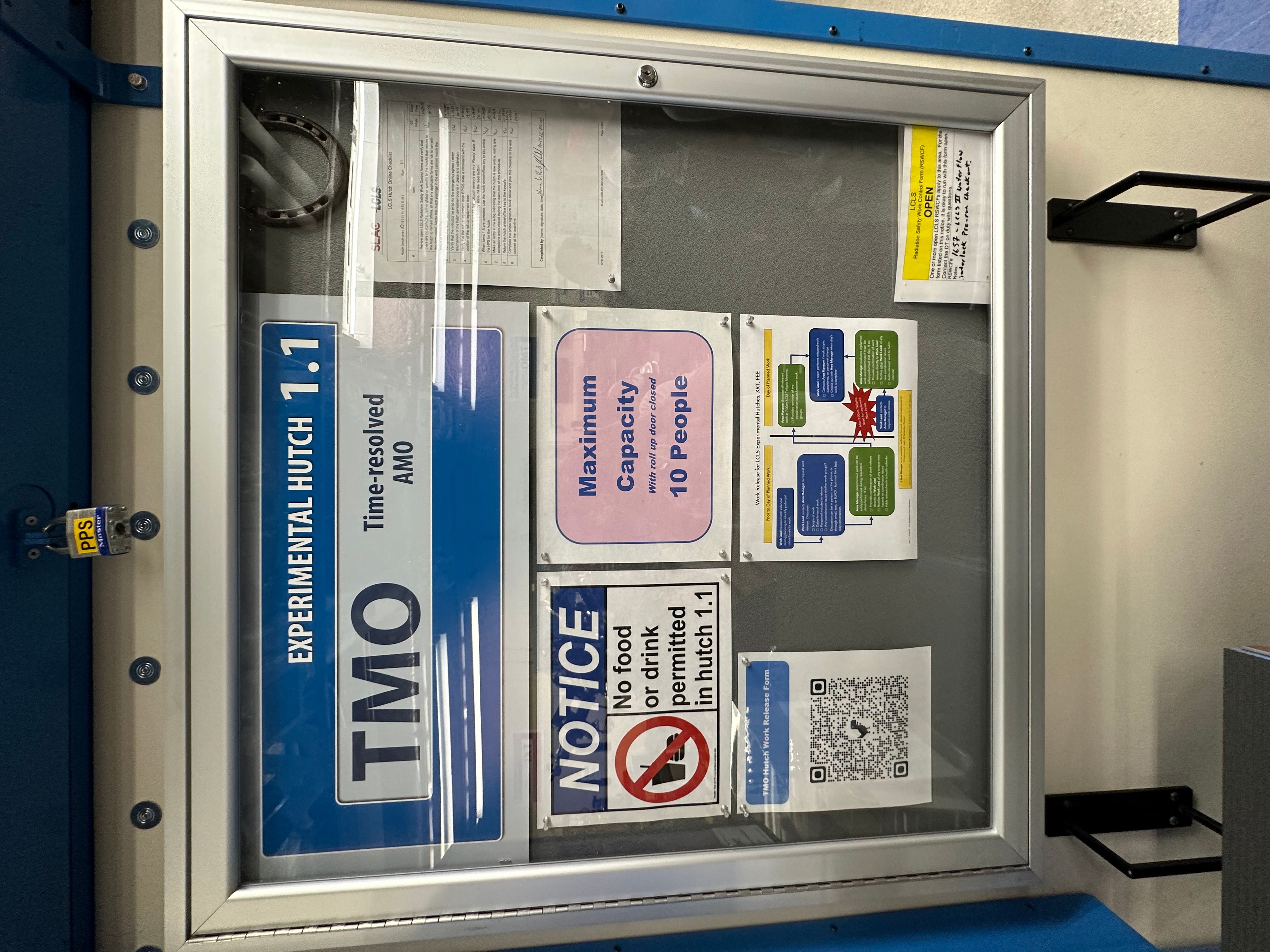

I know this says "hutch" but I read it as "hatch," and imagined Desmond from Lost stuck down here.

Inside the hutch, where they are using the x-ray laser to "record videos of photosynthesis happening." Awesome.

This is what I wish the inside of my garage looked like.

Here's more of the wild and weird machines just sitting in the hallway:

Some warning signs:

A whiteboard where they are presumably working on LeetCode problems while waiting for their turn with the laser.

Another fun facts

And that's it! The tour must end, science must continue. We're delivered back to the original building via bus, and as a final thank-you, we're allowed to make a commemorative flattened penny, which I would have loved to do, but the line was too long.

A few final SLAC notes:

While they were digging up the ground to build the accelerator, they found an intact Paleoparadoxia skeleton - which was an ancient manatee looking thing, and they've kept the big ol' fossil on-site.

Finally, though I did not learn this on the tour, this factoid is too important not to directly rip from Wikipedia:

The SSRL facility was used to reveal hidden text in the Archimedes Palimpsest. X-rays from the synchrotron radiation lightsource caused the iron in the original ink to glow, allowing the researchers to photograph the original document that a Christian monk had scrubbed off.

Palimpsest! My favorite word! Just when you think a place couldn't get any cooler it goes and reveals hidden text on ancient manuscripts.